Any child who heard the phrase “life isn’t fair” growing up was done a disservice. To say this to children is nearly pointless, because no child that needs to be told this is ready to understand its gravity, and no child that understands this needs the cruelty of such a reminder.

Life is unfair in a guttural, maximalist, psychosis-inducing kind of way. Not in a way a child should grasp. As a child, this phrase conjured the image of sick and dead loved ones, especially untimely deaths. Because what could be more more unfair than the randomness of death or illness, and its finality that makes you beg for closure with a ghost?

And maybe there is nothing more unfair. But what happens when it happens to billions, and you know they never had to die this way? And at the same time, just a few million perhaps live an untouchable life–to the point where when confronted with their only boss, death, they play with ideas like the “anti-Christ” and “transhumanism”. Surely, they were able to beat the world, why can’t they beat the universe? They spend their days pursuing physical perfection, perfecting their lineage, and perfecting their assets until they’re forced into bizarre pleasure-seeking activities so they can use up a fraction of the wealth they couldn’t finish in a thousand lifetimes.

When a child dies of starvation, life isn’t just unfair because they die. Life it’s only unfair because the rest of us eat (and waste) so much food. Life is disgustingly unfair because we (honest adults) also know:

- There was food. It was likely walking distance away.

- People decided children would die, generically, but also knew directly which children they would kill. Demographically, geographically, down to the latitudinal coordinates. Adults knew which children would die.

- This child suffered excruciating pain before death

- Their suffering was long and likely spanned their life. These children were vulnerable, and thus suffered before, and then they suffered harder. And then they died.

- This child was someone’s entire world and now their world is over; and finally,

- This child had no idea what was happening, they did not understand how they were dying, and they did not understand why they lived in such misery. Then it ended.

While there are children that lived comfortably and then died acutely–and their deaths are also tragic–the realty that dawns to anyone who has seen this before is that we kill the children we already devalued. There is no competition, but in sometimes in tragedies privileged people who then suffer garner more sympathy, because those who read newspapers and consume news daily are closer to them then the devalued child. It’s important to remember that the children we watch die on our phones are overwhelmingly those already dehumanized. And of course, there are the children we don’t watch die. That do not have the devices or the internet access. The Congo looks like an abyss, being actively blacked out in ways other regions aren’t. How can the land that produces smartphones not produce social media recordings of the crimes committed against its people?

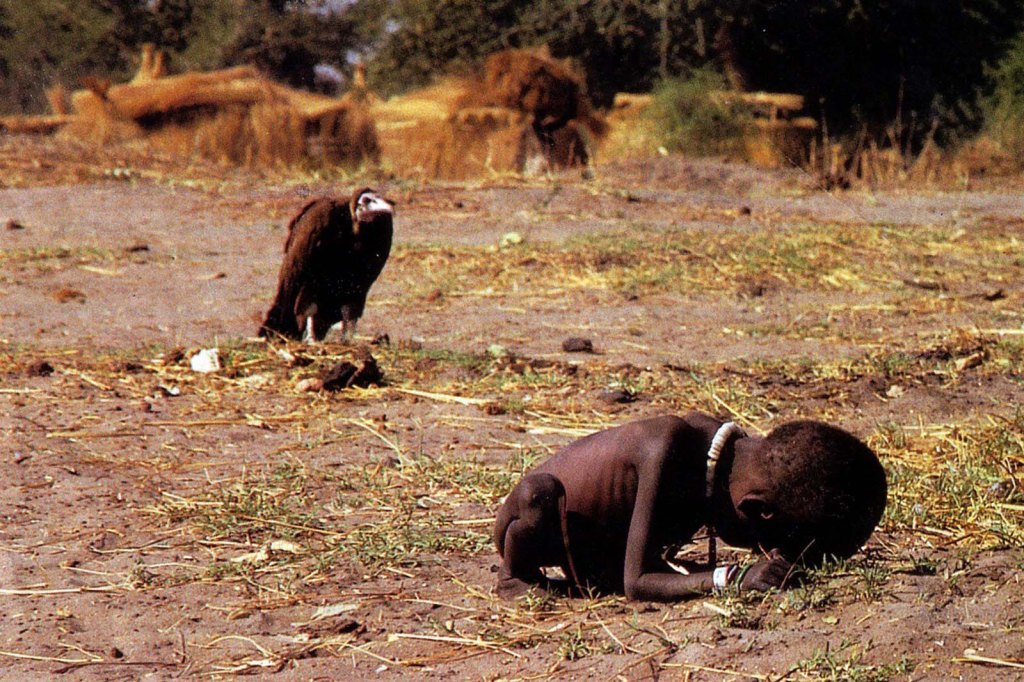

The (in)famous photograph of the small, starving Sudanese child and a vulture in close distance sits forward in my mind, taken by a foreign photographer for a national magazine. Of course I think of the children of Gaza, who I’ve watched die on my phone, whose parents I watched hold their headless bodies more times than my body wants to recall. Maybe the way violence is documented will change humanity’s behavior. Or maybe it will produce more violence–because how many people will weakly watch the powerful destroy humanity and not eventually return that violence in kind?

Apologies for the heavy, unsatisfying read. Most will not be like this.

Ignore my tagline. This is actually a blog about violence disguised behind numbers and computer codes.

Leave a comment